Challenge(s)

How can cities enable safe and inclusive recreational use of urban rivers while managing short-term water quality risks and dangerous user behaviour in a dynamic river environment?

Good practice

Urban, river recreational activities can be managed more safely by combining quick-response environmental monitoring with behavioural data to support timely, evidence-based decisions. By using qPCR water quality testing to detect short-term microbiological risks and sensors to monitor dangerous behaviour such as bridge jumping, authorities can intervene in a targeted and cost-effective way. This approach reduces reliance on large-scale infrastructure investments, supports safe access to water for cooling and recreation, and enables cities to steer river use based on actual conditions rather than delayed or anecdotal information.

This good practice also includes objectives 4.4 (Developing collaborative approaches and drawing on scientific and technologic knowledge from the scientific community and civil society to support decision-making) and 4.5 (Adopting a land management policy that strikes a balance between urban uses and the active port, especially on the waterfront) of the AIVP's Agenda 2030.

Case study

The Connected River project is an EU-funded project that aims to boost the capacities of multi-stakeholder ecosystems to deliver services that guarantee the safety, accessibility, and livability of waterways & waterfronts in the North Sea Region. One of the experiments is taking place in the city of Nijmegen (Netherlands).

The Spiegelwaal in Nijmegen was originally designed as an additional river arm to create more space for water and reduce flood risks along the Waal. Over time, it has evolved into a widely used and socially accepted recreational area. As Nijmegen continues to grow while summers become warmer. Water-based recreation is more popular. Consequently, providing access to safe cooling opportunities has become essential.

Swimming in the Spiegelwaal is actively facilitated and encouraged, as it provides a significantly safer alternative to swimming in the main river channel, where strong currents and large commercial vessels pose serious risks. This makes the Spiegelwaal a preferred location for urban swimming, while simultaneously requiring careful management of health and safety risks.

Water quality management

Water quality in the Spiegelwaal can be affected by short-term contamination events originating from the river system, which may lead to elevated concentrations of harmful pathogens such as E. coli. During such events, swimmers—particularly children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals—face increased risks of gastrointestinal illness, skin infections, and other health complaints.

A structural preventive measure would be to close the inlets connecting the Spiegelwaal to the river during the swimming season. However, manual closure is operationally intensive and costly, while flexible or semi-automated inlet control systems require substantial upfront investments. Moreover, restricting inflow reduces water circulation, which is essential for maintaining ecological balance and overall water quality, creating a trade-off between short-term health protection and long-term environmental sustainability.

The standard monitoring alternative consists of MPN water quality tests conducted twice a week. While reliable, results become available only after up to two days. In a river system with more than seventeen potential upstream contamination sources, pollution peaks can be short-lived and may disappear within 24 hours, meaning warnings often arrive too late to effectively reduce exposure.

To better align monitoring with river dynamics, partners introduced rapid water quality testing using qPCR. In addition to institutional monitoring, local users were actively involved. The rowing club Phocas, located directly at the Spiegelwaal, carried out daily qPCR measurements during the swimming season. This significantly increased data frequency and situational awareness. The method detects both active bacteria and bacteria in a dormant state, which is particularly relevant in Nijmegen, where bacteria may become inactive during downstream transport but can become active again once ingested by swimmers.

The combination of professional oversight and user-led monitoring enabled earlier detection and timely, proportionate responses, such as warning swimmers with a sign at the entries to the swimming location. At the same time, water flow was allowed to remain intact and permanent restrictions or costly infrastructural measures were avoided.

Monitoring and influencing dangerous behaviour

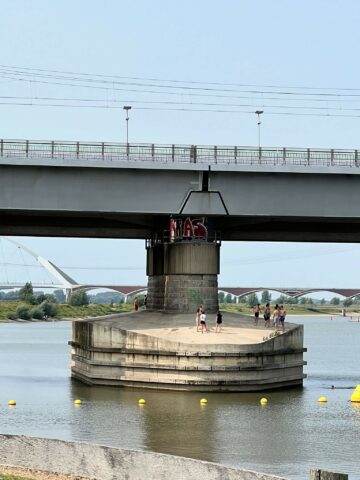

In parallel, sensors were deployed near bridge locations to monitor illegal and risky bridge jumping and associated dangerous situations. Over 10,000 jumps were recorded, far exceeding initial expectations and demonstrating that the behaviour is systematic rather than incidental.

The data revealed that risks extend beyond the act of jumping itself. Dangerous situations can arise from interactions between jumpers and other river users, particularly fishing boats and rowing vessels passing beneath or downstream of the bridge. These interactions often occur unexpectedly, leaving limited reaction time and increasing the risk of collisions or near misses.

By providing objective insight into the frequency, timing and spatial patterns of bridge jumping, sensor data made these interactions visible and measurable. This shifted the focus from incident-based enforcement to understanding behaviour and shared-space dynamics. Authorities used these insights to build a shared understanding of behaviour patterns and risks. The data currently serves as a basis for exploration and dialogue within institutions responsible for managing the area, helping to inform future decisions rather than prescribing specific interventions.

Key insights

By combining rapid water quality testing, behavioural monitoring and active user involvement, the Spiegelwaal pilots demonstrate how data-driven and participatory approaches enable adaptive, cost-effective risk management. Understanding both environmental conditions and user behaviour allows cities to actively steer people towards safer recreational spaces, while preserving accessibility, ecological quality, and the recreational character of urban rivers.