Challenge(s)

How to attract residents, visitors, and businesses to the port city interface zones?

Good practice

Establish cultural clusters

The creation of cultural clusters serves to promote economic development and represents an essential means of raising an area's attractiveness, including in a crisis context. Expanding and combining cultural projects and facilities can inspire a dynamic new movement for the territory concerned, revitalising old port areas and attracting visitors and residents. It also affords an opportunity to improve the quality of life for the city/port interface, and for the city as a whole.

This good practice also includes objective 8.3 (Developing public spaces and recreational or cultural amenities in City Port interface zones to create an appealing new area) of the AIVP's 2030 Agenda.

Case study

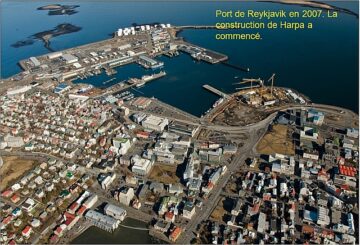

The port of Reykjavik was founded in 1913 and quickly became Iceland’s largest seaport, serving as the country’s primary gateway to the outside world. It was one of the country’s biggest fishing ports until 1962, when the commercial port of Sundahöfn was built east of Reykjavik. The old port then entered a period of transition, during which links with the city were cut off owing to the strict access restrictions imposed on citizens. After 1990, the issue of the relationship between the port and the city became the subject of a wider debate, with growing claims for better access to the port and more areas open to the public.

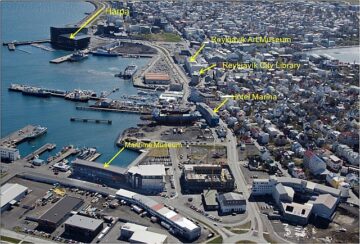

In 1997, the port authorities and the municipality of Reykjavik signed an agreement under which the city would purchase a part of the East Port, along with a part of the Hafnarhús (port house) and the surrounding buildings. The municipality decided to set up Reykjavik’s art museum in the Hafnarhús and to refurbish the nearby public library. There was heated debate about the suggestion of building the, at that time, future “Harpa” concert and conference centre in the East Port, with many people believing that concert halls, museums and other such facilities have no place in a port. The development eventually went ahead, with the addition of a maritime museum that opened in 2003 on the site of a former fish-freezing plant in the West Port. In 2011, the Harpa was inaugurated, designed by Copenhagen architectural firm Henning Larsen, in cooperation with the Icelandic firm Batteríið and the artist Olafur Eliasson. Within the first two years, it hosted two million visitors in cultural events, concerts, and conferences.

The former warehouses of the East Port (Old Harbour) now hold restaurants, shops, and artists’ workshops along with tourism operators. Cooperation between the port and urban authorities and the development of cultural facilities has helped to forge new links between life in the city and the port, thereby helping to make the area more attractive to tourists and locals. The municipality intends to guarantee that the area is used by both groups. Future plans consider minimising nuisance for inhabitants and adapting restaurant hours to work long enough for tourists, but without disrupting locals.

Additional information

- https://www.faxafloahafnir.is/saga/ (Only available in Icelandic)

- Article of Agnieszka Konior https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1206331217750829

- https://listasafnreykjavikur.is/en/hafnarhus

- https://reykjavikcitymuseum.is/reykjavik-maritime-museum/about

- https://henninglarsen.com/en/projects/featured/0676-harpa-concert-hall-and-conference-center

- Konior, A. (2018). The Revitalization of the Old Harbor in Reykjavik by a Cultural Economy. Space and Culture, 21(4), 424-438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331217750829