Interview with Marie-Luce PENCHARD, President of the Supervisory Board, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes (GPMG).

Interview with Marie-Luce PENCHARD, President of the Supervisory Board, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes (GPMG).

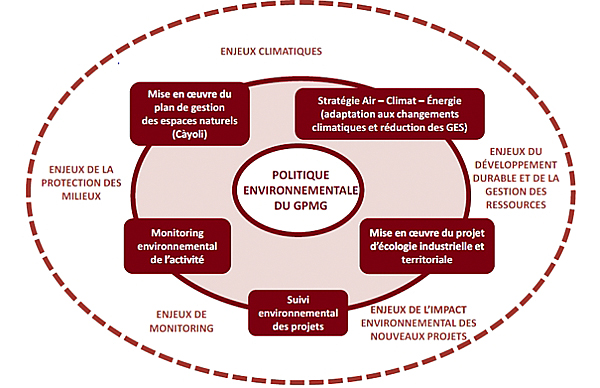

Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes recently ratified the AIVP Agenda 2030. Both the initiatives undertaken by the port in recent years and its current projects are firmly in line with the ten goals that make up our Agenda. This is particularly true of several projects which tie in with three specific Agenda goals, namely adapting to climate change, the energy transition and circular economy, and protecting biodiversity.

GUADELOUPE PORT CARAÏBES is an active member of AIVP since 2009

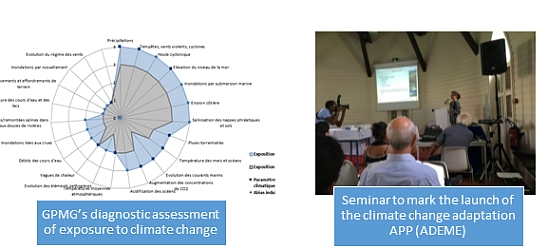

AIVP – Guadeloupe is particularly at risk from the impacts of climate change, and the port especially. Can you remind us of the challenges you are facing and the solutions you are planning or have already implemented, both in terms of the port infrastructures themselves and the City Port interface?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, President of the Supervisory Board, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – Climate change is having a growing impact on natural resources, especially water and aquatic ecosystems. In our Caribbean region, extreme meteorological events are becoming increasingly intense and frequent, threatening territories, economic and social development, and the environment. The Guadeloupe archipelago, in the eastern Caribbean between the tropic of Cancer and the equator, is rich in biodiversity with varied landscapes ranging from mountains and tropical rainforests, to fine sandy beaches, rivers and waterfalls, mangroves, hills, plateaux, coral reefs, and rocky coastline. It is also home to remarkable land and marine wildlife, with numerous endemic species. No fewer than 23 species of whales, dolphins and porpoises protected by international conventions (CITES and the Cartagena Convention) are found in Guadeloupe’s waters.

Guadeloupe is part of the AGOA sanctuary created in 2010, to improve knowledge and supervision of activities that can potentially harm marine mammals.

This rich biodiversity means that the local environment is particularly sensitive to human activities and climate change.

Our infrastructures and port facilities, spread across five sites, are therefore concerned by the issue of global warming for several reasons:

- local agricultural produce exported through the port (fruit, vegetables, sugar cane) is sensitive to climate change;

- extreme climatic events can severely disrupt the port’s activity (interrupting traffic, causing damage, etc.);

- rising sea levels damage concrete surfaces in contact with salt water and cause submersion risks in certain places (notably access roads) and utility networks (power, sewage, etc.).

So adapting to climate change means reducing our vulnerability and exposure to potential impacts on the port, and more generally the associated territories, by:

- protecting residents and direct and indirect users of the port, including those linked to the City/Port interface;

- protecting production facilities and infrastructures;

- protecting the natural environment;

- contributing to mitigation efforts, against a backdrop of rising port activity.

So the Supervisory Board that I chair has designed its five-year strategy around some major ambitions, including adapting to climate change. The adaptation measures taken as part of its Air Climate Energy Plan (PACE) will allow us to limit the cost of its impacts and obtain feedback, so we can then adapt the measures accordingly.

Adaptation measures already taken or planned include:

- direct restoration of natural environments: marine and land ecosystems (mangroves, grassland, coral reefs);

- reducing greenhouse gas emissions and cutting the port’s carbon footprint by developing renewable energies and introducing carbon accounting;

- creating a circular economy in the port community to limit emissions from energy consumption, waste exports and inter-business mobility.

AIVP – You are keen to get the port on board with the energy transition. You also responded to a call for projects issued by the ADEME, with a plan to develop a circular economy in the Industrial Port Zone of Jarry. What are the specific constraints for this territory? And what are the key measures contained in the circular economy programme?

AIVP – You are keen to get the port on board with the energy transition. You also responded to a call for projects issued by the ADEME, with a plan to develop a circular economy in the Industrial Port Zone of Jarry. What are the specific constraints for this territory? And what are the key measures contained in the circular economy programme?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – Published in April 2018, the government’s roadmap for the Circular Economy includes 50 measures, one of which concerns Industrial and Territorial Ecology. Measure 46, for example, aims to strengthen synergies between businesses and promote industrial and territorial ecology in the Regions’ regional plans (PRPGD and SRDEII).

Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes is one of the major players in economic development and trade in Guadeloupe. Currently, almost 95% of the island’s trade passes through its port facilities, notably via the industrial port zone of Jarry, which is home to most of Guadeloupe’s industrial activities in the port logistics and energy generation fields. When we introduced our industrial ecology approach, reaching out to our users and customers, we saw that there was great interest that went beyond the borders of our port.

Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes is one of the major players in economic development and trade in Guadeloupe. Currently, almost 95% of the island’s trade passes through its port facilities, notably via the industrial port zone of Jarry, which is home to most of Guadeloupe’s industrial activities in the port logistics and energy generation fields. When we introduced our industrial ecology approach, reaching out to our users and customers, we saw that there was great interest that went beyond the borders of our port.

There is a large number of actions targeted, all of them necessary in an island environment to generate added value through sharing, recycling, transforming and re-using materials and fluids.

ADEME co-funded studies to determine our plan of actions, which covers issues such as:

- re-use of boxes and pallets: the most sensible solution appears to be to develop a local industry extracting cellulose from card and paper collected at Jarry and in Guadeloupe. In addition, this industry could re-use steam from the thermal generating plant at Jarry;

- local solar power generation and consumption: we also won a call for projects issued by the ADEME in May 2019 concerning the funding of solutions for recharging electric vehicles using renewable energy with a very low impact on the local power network. The 70% funded, €280,000 project will enable us to equip the roof of the passenger terminal, and to install canopies in the parking lot. In addition to supplying power for electric vehicles, the unused surplus electricity will be used to power the terminal.

AIVP – No doubt it would be premature to draw any conclusions on the success of this programme, at this stage. But can you perhaps tell us what obstacles you encountered, and how you overcame them?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – Guadeloupe’s circular economy policy is an economic reality that has been taken on board by businesses and local communities. The issue of waste recycling on our island is a good illustration. Above all, there was a need to develop the way actions resulting from the industrial and territorial ecology programme (EIT) are governed.

To that end, in 2019 Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes participated in the creation of the EIT mission for Guadeloupe as part of SYNERGILE, and became an active member of its steering committee alongside the State, the ADEME and the Local Authorities. We entered into a partnership with SYNERGILE to stimulate the operational deployment of projects, and prevent the risk of EIT initiatives springing up uncoordinated across the same territory.

AIVP – In 2016, you launched a very proactive plan to manage natural spaces, known as the Cáyoli project. You presented the project at our 15th World Conference Cities and Ports, in Rotterdam. What are the main objectives and results of the various actions undertaken?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – Launched in June 2016, the Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes environmental programme marked a turning point in the way environmental issues are treated as central to the port’s activity.

Our commitment to the environment is recognised both nationally and in Europe for its innovative design and ambitious targets, in terms of preserving and restoring natural environments. To give you an idea of the figures involved, the Cáyoli project is a 15 year programme worth €4 million, and aims to preserve 17 hectares of natural environments.

The central principle behind Cáyoli is to adopt a global approach to environmental issues: ecosystems must not be treated as separate, segmented spaces, and the idea is to restore, preserve and maintain the links between them. The social and economic aspects, which I see as fundamental, formed the basis for the programme’s development:

- working in partnership as part of a consultative approach involving the different stakeholders;

- anchoring actions in the long term (planning ahead for the next 15 years);

- promoting coherent green corridors;

- encouraging economic activities generating added environmental value to set up in the port community;

- reconciling environmental preservation with economic development.

Our commitment is very real and practical, with numerous actions already under way. Examples include:

- the creation of a mangrove nursery, with the aim of creating a nursery capable of producing transplantable plants;

President of the Supervisory Board, Marie-Luce PENCHARD, President of the Executive Board, Yves SALAÜN, and the teams working on the social integration project at the charity Yon A Lòt planted the first mangrove trees. Video

- restoration of sea turtle nesting areas near the port zone;

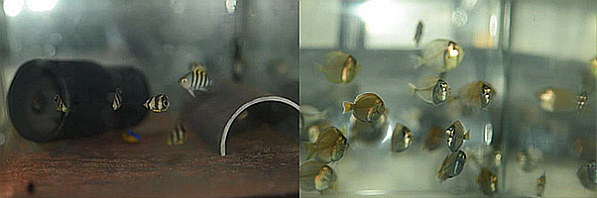

- restoration of coral nurseries capable of producing transplantable coral fragments. Two protected species have already been targeted for preservation and restoration: the Elkhorn (Acropora palmata) and the Staghorn (Acropora Cervocornis)a farm breeding coastal fish post-larvae. Caught in natural environments by fishing, the larvae are raised until large enough to escape predators. Broadly speaking, this farm uses larvae caught in pelagic zones by professional fishermen specialising in this type of fishing. The main objective of the environmental programme is to ensure healthy habitats. The idea is that when environments and healthy and functional, species return to them. However, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes was also keen to focus its efforts on certain coastal species in order to boost fish stocks. In early December, over 800 fish and crustaceans were released into the bay of Petit-Cul-de-Sac-Marin.

Other actions focus on developing sites, their facilities and activities designed to promote their sustainable management, such as installing eco-friendly anchorages, creating an educational undersea trail, and micro-habitats for marine wildlife.

You can read more about these initiatives on the website dedicated to our environmental programme:

https://www.cayoli.fr ; Video

AIVP – The Cáyoli project also includes measures to raise awareness about the important of protecting biodiversity. What forms do the measures take in practice, and what sort of feedback have you had on the actions taken so far?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – Cáyoli Junior, launched in June 2017, is the educational and environmental awareness side of the programme. The principle is simple: to protect the environment effectively, you need to know about it. And it has to be said, that natural coastal environments are often little known.

So we launched Cáyoli Junior with two big events:

- The first was an art competition with secondary school pupils, on the theme of preserving the oceans. A symbolic date was chosen for the prize ceremony: 8 June, which is World Oceans Day.

- The second event was the signing of an agreement with the Chief Education Officer of Guadeloupe, aimed at developing educational tools and awareness projects on the protection of coastal ecosystems.

More specifically, our aim was to:

- co-produce tools to put teaching into context, particularly on the following topics:

- marine biodiversity (remarkable environments and wildlife);

- important maritime issues (history and heritage of GPMG, maritime trade and careers);

- waste (ocean pollution and pioneering solutions);

- organise an annual meeting with pupils around World Oceans Day.

The “I’m Adopting a Mangrove” project, which is both an ecological restoration project and an awareness programme, is part of this wider initiative.

It has been carried out throughout the school year with pupils aged 7 to 10. Video

AIVP – Cáyoli is set to be extended with your Adapt’Island project, selected by the European Union as part of the Life programme. It touches on the issues to do with adapting to climate change mentioned earlier in this interview. To conclude, can you tell us what you are expecting from this project, and how it could affect your climate action plan?

Marie-Luce PENCHARD, Guadeloupe Port Caraïbes – For 10 years, GPMG has been working to integrate environmental issues into the port’s activity. The strategic project adopted for the next five years reflects the organisation’s mature and developed approach to the subject. The aim is to ensure the long-term sustainability of GMPG’s installations and activities, for which an ambitious decision was taken: to base a part of its financial efforts on the development of a new model for adapting to climate change, incorporating nature-based solutions as defined by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature). These solutions will now also be included in our Air Climate Energy Strategy (PACE) being developed as part of the Adapt’Island project.

Nature-based solutions are now among our preferred options for meeting the mitigation and adaptation goals laid down by the Paris Climate Agreement. They are flexible, and represent and economically viable and sustainable alternative, which is often less costly in the long term than investing in technology or building and maintaining infrastructures. They also have the specific advantage of providing multiple benefits, simultaneously tackling the issues of biodiversity erosion and climate change, while offering a realistic technical and economic approach to adapting territories to future living conditions.