Today, it is unquestionable that reaching a sustainable development model for our society, respecting the earth boundaries is (or should be) our main goal. Global initiatives like the SDGs and the AIVP Agenda 2030, inspire and impulse different actors towards this greater goal. But it is easier saying it than doing it, and there are governance challenges along the way, as Prof. Peter Hall shows us in this article. In the coming weeks we will focus on port-city governance processes to learn more about the difficulties that may emerge and the different solutions that ports and cities found to continue this path towards sustainable development.

Throughout its three-decade history, the AIVP Network been a vital forum for the advancing mutual understanding between waterfront city governments and the citizens they represent, and port authorities, corporations and their business partners. AIVP has never shied away from telling an uncomfortable yet liberating truth; namely, that shipping ports and waterfront cities are inextricably tied to each other. A shipping port without a city is a just a harbour without people, place or purpose. A waterfront city without a port is just a residence without consequence, commerce or connection.

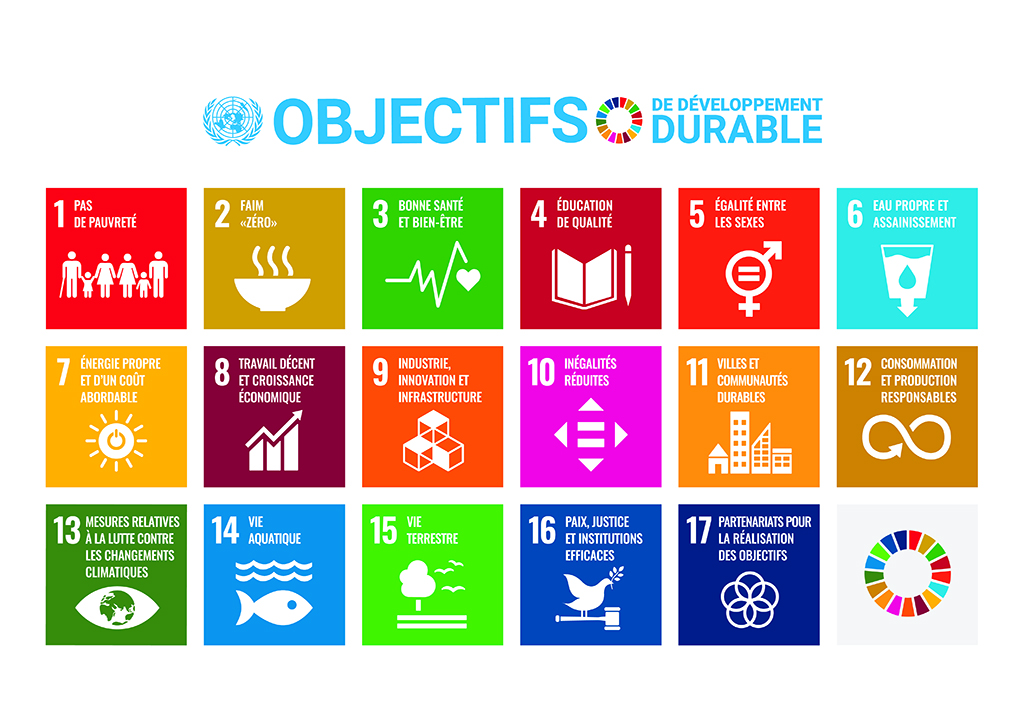

This tough-love message has resonated in port cities across the world, and we have learned a lot over the past decades about how to “plan the city with the port”. The AIVP “Guide of Good Practices” consolidates and regularly updates this experience. Governments, semi-public authorities, private businesses or civil society groups draw on the Guide to improve the spatial organization, environmental and economic performance of port cities. With the adoption and adaptation of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the 2030 Agenda, AIVP has taken this learning forward in exciting and expanding ways.

The SDGs are remarkable because they inform 167 targets that are spelled out in precise and measurable detail. But knowing what outcomes to achieve is not enough, and this is where governance comes in. Governance is about how to make decisions, and who to include in the process.

Despite the clarity of the SDG targets, the path to intended outcomes is often murky. For example, is it better to impose strict environmental standards on the ships that visit a particular port, or is it better to a pursue lower but universally accepted environmental standard for the global shipping industry? Progressive port-city planning might favour the former since it is often easier to secure local political support for measures that improve local air quality; but the UN’s SDG framework (and related climate change strategies) might favour the latter approach. Perhaps a combined or phased approach that builds up trust and establishes precedents is the best implementation strategy, but who is to say?

The best implementation strategies still have to deal with change. Cycles of industrial restructuring leave some waterfront lands abandoned and derelict, and others vulnerable to speculation and conversion by city-builders. As the global community recovers from the pandemic, how will trade routes be reconfigured? Will the desire for high-density urban waterfront living return? How do we balance these changing land use concerns with the SDG’s focus on climate change, ocean preservation and social justice?

And finally, even with better guidance on how to manage change, there will always be challenges in choosing between different options and mitigating their uneven impacts. For example, should those who benefit from increased trade or the relocation of industry away from the waterfront compensate those who experience more truck traffic in their neighbourhoods as a result? The SDGs demand that we pay attention to poverty, inequality and economic growth, which further complicates questions about who wins and who loses because of waterfront and port development.

In other words, knowing what to do is not enough; knowing how to decide is equally important. Governance shifts our attention from deciding what to do and how to do it, to considering how best to make decisions and who to include in the process. Good governance guarantees representation, consultation, transparency, and collaboration by all stakeholders when decisions are made and enacted. Achieving this is easier said than done!

Four governance challenges linked to the SDGs

In concluding, here are four ways that engaging with the SDGs increases the complex governance challenges confronting port cities.

First, the Scale Challenge is well known to port city planners who have to address the impacts of port activities such as trains lines, truck routes and ship anchorages that occur far away from the waterfront and their traditional areas of authority. The SDGs multiply these challenges, because ultimately they are about a set of global solutions to a set of global problems. How much globally-conscious planning can port city citizens take before they start to feel left out, and how can education assist?

Second is the equally well-known Stakeholder Challenge which refers to the large range of stakeholders already involved in port city decision-making, from port authorities, corporations and operators, to municipal governments, urban planners, and citizens. Addressing the SDGs requires the inclusion even more stakeholders, such as waterfront real estate developers, marine environment scientists, global environmental and social justice activists, and more. But collaboration is more easily achieved among small groups with similar interests. How can we achieve inclusion but avoid paralysis by consultation?

Third is the Forum Challenge, which closely related to the scale and stakeholder challenges. Many ports and cities have worked hard to develop forums that promote open communication, consultation and joint decision-making to achieve better outcomes in their port-city. But while networks of ports and cities are learning from each other, it is national governments that sign global climate treaties. In this way, the SDGs have the potential to reshape the established forums. How can we ensure that these changes do not destabilise existing forums and the trust they have accumulated?

And last but not least, there is the Land Challenge. Many of the most challenging dynamics between ports and cities have to do with well-located waterfront land which gives access to trade, recreation, ecology, and a sense of place. How will new and future demands on these lands to accommodate sea level rise, new urban residents, or habitat restoration be handled?

Creating sustainable port cities is a governance challenge, it always has been so; but the adoption and adaptation of the SDGs has made the governance challenge more complex. And that is why it is so welcome to see that Renewed Governance occupies such a central place in the AIVP 2030 Agenda.