The original motivation for the creation of AIVP was exchanging good practices for waterfront redevelopment, after industrial areas lost their original function and could be transformed into new, vibrant urban spaces. Since then, the port-city relationship has become more complex, integrating more environmental, social and economic dimensions, that are reflected on the 10 goals of the AIVP Agenda 2030. However, the port-city interface has remained a key concept for the port-city relationship, while also integrating the new challenges related to the thee dimensions mentioned. Today, the port-city interface is both a space of opportunity and a challenge, is a filter and a meeting point, it is both a physical area and an institutional, environmental, and social membrane where intense interactions between actors take place. Of course, planning this interface is not easy. As we can see in our port cities, some of the original concerns remain: what to do with deactivated port areas? What programs will contribute to a healthy port-city relationship? What planning principles better respond to the concerns connected to sustainable development?

Goal 8 of the AIVP Agenda 2030, concerning the port-city interface, bridges to the other 9 goals, from reducing port nuisances to respecting the port cultural heritage. We should not also forget the challenge that is integrating the port in the urban landscape, developing public spaces or responding to the citizen aspirations for this area. In this dossier, we will learn about what several AIVP members are doing to plan a better port-city interface and the challenges they may have found along the way.

The Port-City Threshold

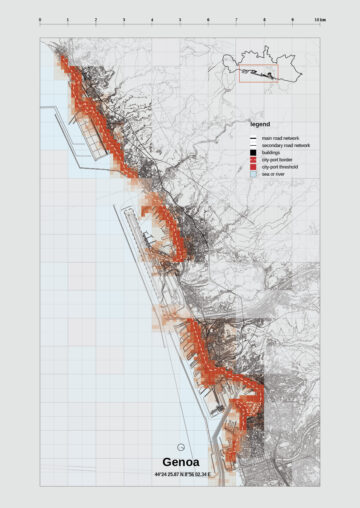

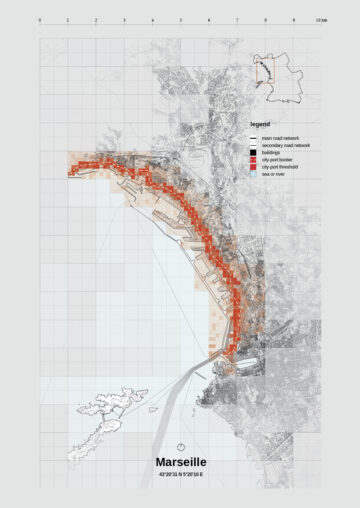

In her article, Dr. Beatrice Moretti, offers us a new perspective on the concept of the Port-City Interface, reinterpreting it as a threshold and design border. She shows us how the port-city threshold is actually a palimpsest of different port and urban functions, while also chronology and a sequence of machines, activities and spaces, and the idea of port-city coexistence can be taken as design attitude attempting to integrate new and pre-existing projects playing with the characteristic ambivalence of the liminal areas.

Maps of the city-port Threshold ©Beatrice Moretti

Brest Métropole: fulfilling the potential of old shipyards

The case of Brest, in France, is good example of how to renovate port urban areas, while remaining connected with the local maritime identity. In the interview with Ms. Quiguer And Mr. Gourtay we learnt how the city managed to introduce new uses in a crucial waterfront location, creating a 2.7 hectare hub of culture while also aiming at the “eco-district” label, and holding a consultation process with the local citizens.

Port-Saint-Louis du Rhône: from brownfield to welcoming the yachting industry

Transformative port-city processes are usually complex and include many stages before the actual design is prepared. In the interview with Mr. Martial Alvarez, Mayor of Port-Saint-Louis du Rhône, France, we learn about it is important to lay the foundations for future ambitious development, by preparing environmental surveys, cleaning operations and negotiation with key actors. In this case, the goal was to develop a major plan focused on sailing and seafood-related activities, with special emphasis on the yachting industry.

Transforming the waterfront: new solutions for new challenges

In January we were fortunate to host an excellent webinar, including a discussion with Algeciras, Barcelona, San Antonio, and the Spanish ministry of urban development concerning the challenges they have faced to develop new functions on the waterfront. We could learn that the learning process is constant, and we always reflect on what has been done and how it can be improved to respond to new demands, as the New Urban Agenda.

Enhancing the aesthetic values of ports

Economy, GDP impact, tons of cargo throughput, jobs. These have been the key indicators to assess the success of a port. Focusing on efficiency for decades has led many ports to neglect other non-economic values, with consequences for the port landscape, its architecture and image. However, there are new approaches, as explained in this article by Dr. José M Pagés Sánchez, and we can learn from them.

Helsinki: acting on the environmental, social, and urban planning levels of the Interface

In her article, Satu Aatra explains us in her article how the port of Helsinki is facing the different challenges emerging from the port-city coexistence. Since the port-city relationship cannot be simplified to the physical interaction, we learn about the different projects developed to make the port of Helsinki a good neighbour.

Integrating the port in the landscape of Oslo

The port of Oslo has been leading the quest for a coherent port image that integrates aesthetic values. For that reason, the port authority decided some years ago to develop aesthetic guidelines for development of a port, including both urban waterfront areas with former port activities and the active terminals. In this article by Hans Kristian Riise we learn first-hand what has been done and how have these guidelines been applied.

Inspiring testimonies that will surely impulse new ideas in port cities all over the world. We hope you enjoy the reading, and watching, of these interventions and that they are useful to ongoing and future discussions concerning your port-city interface.